Trying to get more vegetables into your diet but getting bored with broccoli and spinach? There’s a whole category of super-nutritious vegetables you may be overlooking. Sea vegetables, otherwise known as seaweed, are a great way to add variety to your five-a-day routine. You can add sea vegetables to soups or stir-fries or make a seaweed salad instead of the same old tossed salad. You can even use seaweed to make nutritious—and addictive—chips to snack on.

This article is also available as a podcast. Click to listen

What Kinds of Seaweed are Good to Eat?

As with land vegetables, there are lots of different kinds of sea vegetables, with various flavors and textures. Some are soft, others are chewy; some are mild, others very briny. Here’s a brief guide to some common sea vegetables.

What Are the Different Types of Sea Vegetables?

Alaria is harvested in the Atlantic and is a distant cousin of Japanese wakame. It has a fairly pronounced briney flavor and a chewy, slightly rubbery texture.

Arame is a delicately textured plant that grows wild off the coast of Japan. It has a soft texture and bland flavor that reminds me of very thin cooked buckwheat noodles.

Dulce, with its broad, reddish-brown fronds, is harvested off the Atlantic coast of Maine. It has a medium strong, somewhat smoky flavor.

Hijiki is a dark, small-leaved seaweed from Japan that resembles dried tobacco. It has a tender-crisp texture and a very mild, almost sweet flavor.

Kombu, or kelp, is a broad-leafed variety that grows wild in the very northernmost region of Japan’s Arctic sea. It’s often used in stocks or ground as a flavor enhancer.

Wakame is a tender, dark-green seaweed that is harvested in Japan. It has a mild flavor and a texture similar to cooked spinach.

What are the Nutritional Benefits of Seaweed?

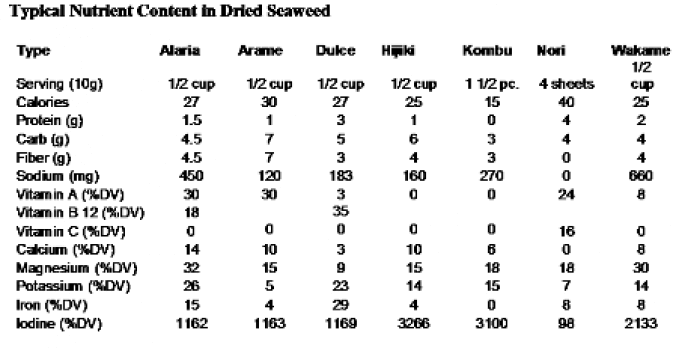

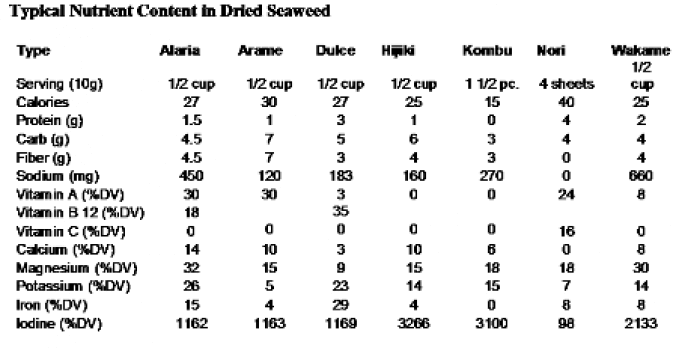

The nutritional profile of different types of seaweed varies as well. In general, sea vegetables are low in calories and contain a variety of minerals including calcium, magnesium, and potassium. Dulce and alaria, are quite high in iron and vitamin B12, which makes them particularly good choices for vegans who may otherwise have difficulty getting these nutrients.

Some—but not all—types of seaweed are high in sodium. For example, alaria and wakame are both high in sodium, but arame and hijiki are quite low.

Can You Get Too Much Iodine from Seaweed?

Most types of seaweed also contain iodine, a nutrient that’s important for healthy thyroid and neurological function. Iodized salt is the primary source of iodine in American diets. If you use a natural sea salt instead of iodized salt, including seaweed in your diet can be a good way to be sure you’re getting enough of this important nutrient. But more is not always better. Although iodine is needed for healthy thyroid function, too much iodine can also interfere with your thyroid.

A serving or two per day of seaweed won’t cause a problem for most people. But just to be on the safe side, I suggest avoid eating large amounts of seaweed every single day, particularly kombu or hijiki, which are particularly high in iodine. Dried kelp granules, which are often sold as a salt substitute, are also a potent source of iodine. A quarter teaspoon can provide two or three times the suggested upper limit for iodine intake, so you don’t want to overdo that either.

Where Can You Buy Seaweed?

Dehydrated seaweed is the easiest to find. You may find one or two types in the international aisle of your local grocery store. You’ll probably find a larger selection at a health food store or a natural foods grocer. The best prices and selection are usually found at Asian groceries or markets, where they might even have fresh or frozen seaweed, which is otherwise fairly hard to find. If you’re having trouble finding a good selection, you can also shop online from the sources listed below in the Resources section. Keep a few packages of dried seaweed on hand for those times when you run out of fresh vegetables and don’t have time to make it to the market.

How Do You Prepare Seaweed?

Many dehydrated sea vegetables are ready to use in salads, soups, or stir-fries after a brief soak in cool water; others need to be boiled for a few minutes. Soaking seaweed in water is also a way to reduce the sodium content, although you may end up losing some of the other minerals as well.

Some varieties don’t even need to be rehydrated. For example, dehydrated dulce can be eaten right out of the bag—it tastes sort of like jerky. Or, sauté pieces of dulce in a bit of olive oil until they’re crisp. You can eat it instead of chips, use it in place of the bacon in a BLT, or crumble it over a baked potato.

This article was originally published on QuickandDirtyTips.com

Q. I’ve read a lot about the health benefits of Vitamin D. But isn’t there also a limit of how much Vitamin D I should supplement? Is there a danger or limit that avoids a possible toxic amount?

Q. I’ve read a lot about the health benefits of Vitamin D. But isn’t there also a limit of how much Vitamin D I should supplement? Is there a danger or limit that avoids a possible toxic amount? Q. In your podcast on mineral water, you said that tap water can be a source of minerals such as calcium and magnesium. If I use a water filtration pitcher to filter my tap water, am I removing these nutrients?

Q. In your podcast on mineral water, you said that tap water can be a source of minerals such as calcium and magnesium. If I use a water filtration pitcher to filter my tap water, am I removing these nutrients?