As you may have noticed, whether I’m talking about reducing your risk of heart disease, preventing Type 2 diabetes, or slowing the aging process, one piece of advice keeps coming up over and over again: Maintain a healthy weight. Of course I realize that this is a lot easier said than done. In order to lose weight, you have to eat less and when you eat less you usually feel hungry, which most of us find unpleasant. So this week, I have some tips for you on how to eat fewer calories without feeling hungry.

As you may have noticed, whether I’m talking about reducing your risk of heart disease, preventing Type 2 diabetes, or slowing the aging process, one piece of advice keeps coming up over and over again: Maintain a healthy weight. Of course I realize that this is a lot easier said than done. In order to lose weight, you have to eat less and when you eat less you usually feel hungry, which most of us find unpleasant. So this week, I have some tips for you on how to eat fewer calories without feeling hungry.

Category: Healthy Eating Tips

Practical tips for improving your nutrition

Dessert Rules

Q. I am a healthy, active person trying to maintain my weight. About once or twice a week I will have a nice dessert at my favorite bakery, staying within my allotted calories for the day. My question is: though I’m keeping calories down, is it still healthy?

Q. I am a healthy, active person trying to maintain my weight. About once or twice a week I will have a nice dessert at my favorite bakery, staying within my allotted calories for the day. My question is: though I’m keeping calories down, is it still healthy?

A. Well, sweets aren’t exactly health-promoting. Nonetheless, But I do believe that a healthy diet can include the occasional sweet treat. Here are my guidelines:

This Week’s Podcast: Cooking With Oil

I’ve talked about the pros and cons of various oils and how to store oils in previous podcasts but several of you have asked me to talk more specifically about what happens to oils when you heat them up and which ones are safest to cook with. Find out how to avoid the formation of harmful chemicals when cooking with oil in this week’s show.

I’ve talked about the pros and cons of various oils and how to store oils in previous podcasts but several of you have asked me to talk more specifically about what happens to oils when you heat them up and which ones are safest to cook with. Find out how to avoid the formation of harmful chemicals when cooking with oil in this week’s show.

Resolution Rescue: What Are You Craving?

If losing weight is one of your New Year’s resolutions, sooner or later you’ll probably find your resolve tested by an overwhelming desire for something really naughty. Hopefully, you’ll reach for a diet-friendly snack instead. But your chances of heading off dietary disaster will be higher if you choose an alternative that is a good match for your particular craving.

If losing weight is one of your New Year’s resolutions, sooner or later you’ll probably find your resolve tested by an overwhelming desire for something really naughty. Hopefully, you’ll reach for a diet-friendly snack instead. But your chances of heading off dietary disaster will be higher if you choose an alternative that is a good match for your particular craving.

if you’re craving chocolate, for example, another stick of celery is probably not going to do the trick. (Then again, if you’re craving something salty, it just might.)

Here are some foods to help satisfy various cravings without ruining your diet:

Is Chicken Less Inflammatory Than Beef?

You’ll find lots of articles in the popular press about the value of anti-inflammatory diets. But many of them perpetuate certain myths about food and inflammation–in particular, that red meat is inflammatory and chicken is anti-inflammatory. I think that’s because many people simply assume that all the foods that we’re used to thinking of as “healthy” are anti-inflammatory and foods that we have been trained to view as “unhealthy” are inflammatory. In reality, the research on foods and inflammation challenges some of these assumptions.

You’ll find lots of articles in the popular press about the value of anti-inflammatory diets. But many of them perpetuate certain myths about food and inflammation–in particular, that red meat is inflammatory and chicken is anti-inflammatory. I think that’s because many people simply assume that all the foods that we’re used to thinking of as “healthy” are anti-inflammatory and foods that we have been trained to view as “unhealthy” are inflammatory. In reality, the research on foods and inflammation challenges some of these assumptions.

A boneless, skinless chicken breast–that Holy Grail of diet food–is low in total fat and saturated fat, it’s true. But that’s not the whole story. Chicken is also relatively high in omega-6 fats, including arachidonic acid, a fatty acid that directly feeds cellular production of inflammatory chemicals. Continue reading “Is Chicken Less Inflammatory Than Beef?”

Trying to eat more veggies? Don’t forget about sea vegetables!

Trying to get more vegetables into your diet but getting bored with broccoli and spinach? There’s a whole category of super-nutritious vegetables you may be overlooking. Sea vegetables, otherwise known as seaweed, are a great way to add variety to your five-a-day routine. You can add sea vegetables to soups or stir-fries or make a seaweed salad instead of the same old tossed salad. You can even use seaweed to make nutritious—and addictive—chips to snack on.

This article is also available as a podcast. Click to listen

What Kinds of Seaweed are Good to Eat?

As with land vegetables, there are lots of different kinds of sea vegetables, with various flavors and textures. Some are soft, others are chewy; some are mild, others very briny. Here’s a brief guide to some common sea vegetables.

What Are the Different Types of Sea Vegetables?

Alaria is harvested in the Atlantic and is a distant cousin of Japanese wakame. It has a fairly pronounced briney flavor and a chewy, slightly rubbery texture.

Arame is a delicately textured plant that grows wild off the coast of Japan. It has a soft texture and bland flavor that reminds me of very thin cooked buckwheat noodles.

Dulce, with its broad, reddish-brown fronds, is harvested off the Atlantic coast of Maine. It has a medium strong, somewhat smoky flavor.

Hijiki is a dark, small-leaved seaweed from Japan that resembles dried tobacco. It has a tender-crisp texture and a very mild, almost sweet flavor.

Kombu, or kelp, is a broad-leafed variety that grows wild in the very northernmost region of Japan’s Arctic sea. It’s often used in stocks or ground as a flavor enhancer.

Wakame is a tender, dark-green seaweed that is harvested in Japan. It has a mild flavor and a texture similar to cooked spinach.

What are the Nutritional Benefits of Seaweed?

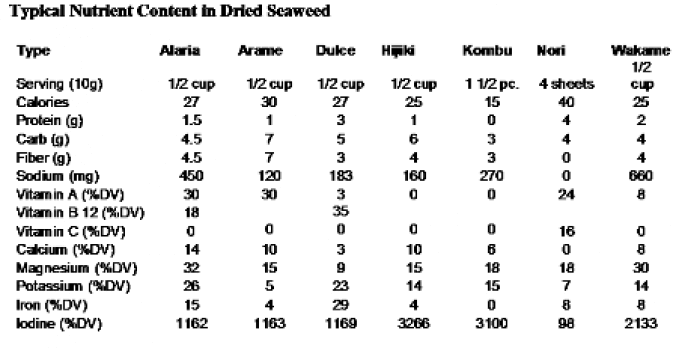

The nutritional profile of different types of seaweed varies as well. In general, sea vegetables are low in calories and contain a variety of minerals including calcium, magnesium, and potassium. Dulce and alaria, are quite high in iron and vitamin B12, which makes them particularly good choices for vegans who may otherwise have difficulty getting these nutrients.

Some—but not all—types of seaweed are high in sodium. For example, alaria and wakame are both high in sodium, but arame and hijiki are quite low.

Can You Get Too Much Iodine from Seaweed?

Most types of seaweed also contain iodine, a nutrient that’s important for healthy thyroid and neurological function. Iodized salt is the primary source of iodine in American diets. If you use a natural sea salt instead of iodized salt, including seaweed in your diet can be a good way to be sure you’re getting enough of this important nutrient. But more is not always better. Although iodine is needed for healthy thyroid function, too much iodine can also interfere with your thyroid.

A serving or two per day of seaweed won’t cause a problem for most people. But just to be on the safe side, I suggest avoid eating large amounts of seaweed every single day, particularly kombu or hijiki, which are particularly high in iodine. Dried kelp granules, which are often sold as a salt substitute, are also a potent source of iodine. A quarter teaspoon can provide two or three times the suggested upper limit for iodine intake, so you don’t want to overdo that either.

Where Can You Buy Seaweed?

Dehydrated seaweed is the easiest to find. You may find one or two types in the international aisle of your local grocery store. You’ll probably find a larger selection at a health food store or a natural foods grocer. The best prices and selection are usually found at Asian groceries or markets, where they might even have fresh or frozen seaweed, which is otherwise fairly hard to find. If you’re having trouble finding a good selection, you can also shop online from the sources listed below in the Resources section. Keep a few packages of dried seaweed on hand for those times when you run out of fresh vegetables and don’t have time to make it to the market.

How Do You Prepare Seaweed?

Many dehydrated sea vegetables are ready to use in salads, soups, or stir-fries after a brief soak in cool water; others need to be boiled for a few minutes. Soaking seaweed in water is also a way to reduce the sodium content, although you may end up losing some of the other minerals as well.

Some varieties don’t even need to be rehydrated. For example, dehydrated dulce can be eaten right out of the bag—it tastes sort of like jerky. Or, sauté pieces of dulce in a bit of olive oil until they’re crisp. You can eat it instead of chips, use it in place of the bacon in a BLT, or crumble it over a baked potato.

This article was originally published on QuickandDirtyTips.com

Nutritional medicine is (finally) focusing on food

[Archival: Originally published on my (discontinued) NutritionData.com blog]

As we head into the second day of the Nutrition and Health Conference, I can’t help but reflect what a difference a decade makes.

Ten years ago, conferences like this one were dominated by research and presentations about individual nutrients, like tocotrienols or pycnogenol. The protocols all involved cocktails of high dose nutritional supplements. The exhibit hall was filled with supplement manufacturers.

This week, I haven’t heard a single presentation (and seen only a handful of slides) about isolated nutrients. Instead, the focus is on food. The research and protocols all address what foods make up the diet, how they are prepared, processed, combined, and balanced to promote health. And out in the exhibition hall? Vital Choice Wild Seafood, POM pomegranate juice, Pistachio Health.com, and the Washington Red Raspberry commission.

What’s more, we’re finally looking at the big picture rather than individual “super foods.” The title of a talk I’m headed to right now says it all: “Preventing Cancer with Food: Magic Bullets vs. Dietary Patterns.” (presented by Marjorie McCullough from Emory University.)

Finally, nutritional medicine is about food.

How safe is imported fish?

Q. Is imported frozen fish from countries like India and Vietnam safe? I avoid buying any food imported from China but I bought frozen Swai Basa Fish (farmed) from Vietnam and frozen Squid (caught wild) from India. They tasted really good and they were cheap, but I’m wondering if we can trust those imports or they may be full of some toxic stuff.

Q. Is imported frozen fish from countries like India and Vietnam safe? I avoid buying any food imported from China but I bought frozen Swai Basa Fish (farmed) from Vietnam and frozen Squid (caught wild) from India. They tasted really good and they were cheap, but I’m wondering if we can trust those imports or they may be full of some toxic stuff.

A. Theoretically, the safety of fish being sold in U.S. markets is monitored by federal agencies such as the FDA, whose job it is to be sure that the fish sold for human consumption in the U.S is “safe, wholesome, and not misbranded or deceptively packaged.” (Institute of Medicine on Seafood Safety)

But as we’ve seen lately, the ability of the FDA to effectively police the food supply and enforce its regulations is in serious doubt. Just a few years ago, for example, there was a scandal in which salmon being sold for a premium as “wild-caught” in both wholesale and retail markets turned out to be cheap farmed salmon. ( Story from New York Times)

To make things even more challenging, fishing and farming practices are changing rapidly around the globe as demand for seafood increases. New restrictions and best practices are being implemented. But loopholes and work-arounds are also constantly being discovered and exploited. It’s a moving target!

The best resource I’ve found to keep up with these issues is Seafood Watch. These guys are working hard to stay on top of all of these issues and to provide up-to-date resources for consumers trying to make safe and responsible choices.

I scanned Seafood Watch’s reports on both the fish you mentioned. In terms of toxins or contaminants, I didn’t see too much to worry about with the wild-caught squid, but these comments on farmed swai basa got my attention:

“Commercial aquaculture for finfish in Viet Nam continues to use relatively low technology and many operations continue to use homemade feeds…[with] little or no management of aquaculture operations…”

The safety of these fish as food obviously depends primarily on the water they’re raised in and the food they are fed. They might be perfectly fine, but it doesn’t look as if anyone is paying too much attention.

From a sustainability perspective, which is more about the long-term health of the oceans than the safety of the food, both wild-caught squid and farmed swai basa are considered “good alternatives” but not “best choices.”